|

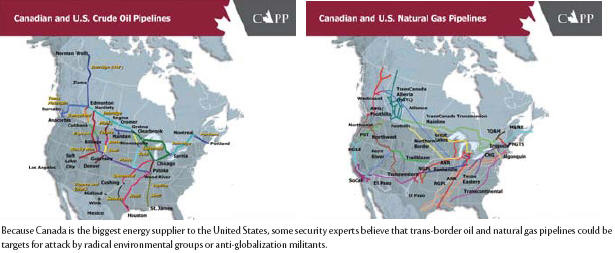

HOMELAND SECURITY infrastructure HOW SAFE IS CANADA’S ENERGY INFRASTRUCTURE?SINCE SEPT. 11, 2001, CANADA HAS TAKEN NUMEROUS STEPS TO BOLSTER ENERGY INFRASTRUCTURE SECURITY. BUT HAS ENOUGH BEEN DONE? www.mcgraw-hillhomelandsecurity.com By Levon Sevunts Christian Latreille couldn’t believe his eyes as he entered one of the world’s largest hydroelectric stations, the LG-2, a sprawling underground facility 600 feet beneath the frozen wilderness in Quebec. Latreille, a hard-hitting journalist with the French-language public broadcaster Radio-Canada, and his cameraman had just literally walked into what should have been a secure facility. Yet to their astonishment, nobody challenged them at the power station that produces electricity for 1.3 million Quebecers, as well as exporting energy to many more in New England. "I had this image in my head of thousands and thousands of Quebecers in their living rooms watching TV and me having the power of cutting the power," Latreille said. "And I knew exactly which button to press." But that wasn’t all. Latreille and his cameraman then drove another 1,250 miles to a different set of hydroelectric facilities owned and operated by Hydro- Quebec, one of Canada’s largest public utilities. Amazingly, the same scenario was repeated at the Manic, Quebec, set of hydroelectric facilities, Latreille said. The ease with which Latreille and his cameraman were able to gain access to the sensitive sites caused an uproar when their documentary aired in February. It also raised serious questions about the security of Canada’s energy infrastructure, which stretches over hundreds of thousands of miles in often remote and inaccessible locations. The embarrassed premier of Quebec, Jean Charest, who learned of the documentary’s existence only after watching it on TV, fired Public Security Minister Jacques Chagnon and Natural Resources Minister Sam Hamad, whose portfolio included responsibility for Hydro-Quebec. André Caille, the Hydro-Quebec CEO, also lost his job. Hydro-Quebec spokesman Sylvain Théberge said that the company has undertaken an extensive review of its security and plans to make an announcement on the matter later this year. But until then, Théberge said, he could not discuss details of the new security plan. He said only that Hydro-Quebec is evaluating a state-of-the-art surveillance system for its critical facilities, and that the utility has hired security guards for its sensitive sites. Latreille said Hydro-Quebec has hired a new chief of security,Mario Laprise, a former top provincial cop. "He’s got a great reputation [for] fighting organized crime," said Latreille, who is working on a followup story focusing on security measures taken by Hydro-Quebec in response to his documentary. "But many experts in industrial security say it’s not the right approach. Hydro-Quebec is not a country: Hydro-Quebec is an industrial company, and you don’t need a police approach to protect dams. You need an industrial security approach." Latreille’s documentary also resulted in calls for a greater involvement by the federal government in protecting Canada’s security infrastructure. The Right Approach? But Janet Bax, senior director at the Infrastructure Assurance Program at the department of Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness Canada (PSEPC), the Canadian equivalent of the U.S. Department of Homeland Security, said focusing too much on terrorist threats to the exclusion of all others is likely to do more harm than good. Instead, Canada has adopted an all-hazards approach to securing its critical infrastructure. Forest fires, floods, landslides, tsunamis, avian flu, and SARS are hazards that are more likely to occur than a terrorist attack, Bax said. At the same time, PSEPC has created an Integrated Threat Assessment Center (ITAC) that analyzes and communicates all kinds of threats to the infrastructure operators, Bax said. Michel Juneau-Katsuya, a former high-ranking official with the Canadian Security Intelligence Service (CSIS) who now runs his own corporate security and intelligence-consulting firm, says that a threat and risk assessment can be described as a "threat to and threat from" exercise. While most security people can do a decent "threat to" assessment—identifying critical pieces of equipment or information that have to be protected —only a small number can do the "threat from" assessment: the "Who wants to hurt me?" part that comes from a good intelligence assessment. "When you compare the two things together, you realize that the Latreille incident was just a media show," said Juneau-Katsuya. His company, The Northgate Group Corp., was hired by Hydro-Quebec to help create a viable security plan. Juneau-Katsuya said radical Islamic terrorists have, so far, not been interested in targeting critical infrastructure in Canada. The terrorists want to hit a symbol of a nation, kill people and promote fear. Currently, infrastructure, which would have more of a military or economic value, is not in their plans. On the other hand, sabotage of the critical energy infrastructure by radical environmentalist groups, antiglobalization militants or simply disgruntled employees is of greater concern than the threat from Islamic terrorist groups, Juneau-Katsuya said. Canada already has had to deal with radical environmentalist sabotage of its lumber industry, Juneau-Katsuya noted. In addition, Canada’s energy infrastructure could be targeted by anti-globalization radicals because it exports to the United States. Last year, a previously unknown group claimed responsibility for the bombing of a high-tension tower transporting energy to the United States. The amateurish bombing caused little damage and did not interrupt the flow of electricity, but it did cause a public relations headache for Hydro-Quebec. In the United States itself, there were five sabotage attempts against the electricity transporting infrastructure last year, Juneau-Katsuya said. "Are we witnessing an emergence of a trend? We’re not sure yet; we don’t have enough information," he said. "But it looks like some people might have identified transportation of electricity as a weak point." Government Safeguards Greg Stringham, vice president of the Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers (CAPP), which represents about 150 oil and gas producing companies, said Canada remains the most reliable and biggest energy supplier to the United States. According to CAPP, Canada supplies 15 percent of U.S. gas needs and 10 percent of its oil needs. The oil and gas industry always has been very strong when it comes to emergency response, said Stringham, whose association assists in security coordination within the industry. The industry has filed and tested detailed plans of how to deal with different contingencies, ranging from industrial accidents to natural disasters or terrorist attacks, he said. "But Sept. 11, 2001, was a big wake-up event for everyone, and it caused us to start looking at what we can do proactively," he said. The industry got together with the Canadian and U.S. governments to organize a two-way communications system, as well as a precise communications protocol with a common threat vocabulary, which would allow the members not only to receive information about possible threats but also distribute information from their sources, Stringham said. CAPP has been looking at safety and security around the industry’s critical infrastructure, he added. The industry has more than 120,000 oil and gas-producing wells and hundreds of thousands of miles of redundant pipelines, Stringham said.

Even major gas and oil pipelines have multiple parallel lines, which adds to the reliability of the entire system. At the same time, the industry is working with closely governments to make sure that the critical points in the system are well protected, Stringham added. CAPP, in consultation with the Alberta government, has established a "best practices" security guidebook for facilities at different levels of alert. The Alberta Counter-Terrorism Crisis Management Plan was the biggest piece of work that the oil and gas industry has done in conjunction with the Alberta government, Stringham said. "Having said that, there has never been a need to use that plan, and there has never been a threat we are aware of in Canada," Stringham continued. "But it’s good to be prepared." In addition, the federal and provincial governments across Canada have set up a secret list of the critical infrastructure, Stringham said. CAPP also works closely with the Security Information Management Unit established by the office of Alberta’s solicitor general. This organization gathers intelligence and sets threat levels for the province. Is a Private-Sector Solution Preferred? But instead of adding new layers of bureaucracy, Juneau-Katsuya suggests creating an independent privatesector organization that would deal with the security needs of the energy industry. That private-sector organization would be better suited than government to deal with the three major components of risk management: risk assessment, risk mitigation and risk transfer, the most neglected of three, Juneau-Katsuya said. Juneau-Katsuya argued that a private organization modeled after U.S. Information Sharing and Analysis Centers, but with more emphasis on intelligence analysis, would be far more effective than another government-run bureaucracy. "I think one of the problems that we have in Canada is that we’re still in the old paradigm that the government is the solution to these things. I disagree. Security is everybody’s business. The private sector must get involved." .Levon Sevunts is a Canadian journalist who has written about homeland security issues for numerous publications.

|