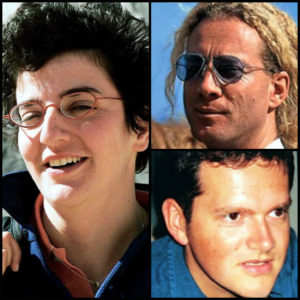

On November 11, 2001, I survived an ambush that killed three of my colleagues. Johanne Sutton, Pierre Billaud and Volker Handloik were killed when the group of Northern Alliance soldiers we were traveling with was ambushed by Taliban fighters on a barren plateau near Dasht-e-Qala in Takhar Province, in northeastern Afghanistan.

Jo, Pierre and Volker were the first journalists to be killed in that war. But since 2001, at least 120 local and foreign journalists have lost their lives in the line of duty, according to the Afghanistan Journalists Federation.

Between 2010 and 2021, 87 Afghan journalists were killed in the course of their duties, and in 2021 alone, 13 journalists and media workers lost their lives, according to the International Federation of Journalists.

This is the dispatch I filed to the Montreal Gazette on the following day, on November 12 (on my birthday) 2001.

The day I almost died

CHAGHATAY, Afghanistan – Johanne’s bullet-riddled body lay sprawled on the back of a Russian-made armoured personnel carrier, her dead eyes staring into the billions of stars in the Afghan sky.

There was nothing I could do for her but to tie a piece of cloth around her head to close her half-open mouth and hold her lifeless hand for one last bumpy ride on Afghan roads.

I met Johanne Sutton, a soft-spoken 35-year-old reporter for Radio France International, at a press conference by Dr. Abdullah Abdullah, the Northern Alliance Foreign Minister. He was late flying from the Panjshir Valley, so Johanne and I spent about four hours chatting.

Then I ran into her at Commander Mamur Hassan’s house, in Dasht-e Qala, just two days before she and two other journalists were killed.

Sunday, Nov. 11, went badly for me from the beginning. I got lost, fell into a mudhole and was laughed at by half of the population of Khojabhuddin. With both my computer and my satellite phone crushed, I had to borrow a colleague’s phone to dictate a story just before deadline.

Otherwise, it was like any other day in my two weeks in Afghanistan. Together with my translator, Massoud, we went to the one-storey compound of the Foreign Ministry in Khojabhuddin to get permission to visit the front lines on the Chaghatay Hill, where we were expecting one last push by the Northern Alliance forces to take a strategic Taliban hilltop stronghold.

Most of the reporters were not allowed to visit the front line during the first night of the offensive, but on Saturday the trenches on Chaghatay were full of them.

I knew most of them by first name only. We would run into each other during rare press conferences or on the front lines.

In the forward trenches I ran into Paul McGeough, a Sydney Morning Herald reporter, and Volker Handoik, a 40-year-old writer for Stern, a German magazine. You simply could not miss Volker — in the crowd of dark faces and black hair, Volker’s long, curly blond hair, tied in a knot in the back, stuck out like an orange warning signal. He was wearing a long cotton-filled Uzbek coat over his Western clothes, which made him stand out even more.

I had met both of them at Commander Hassan’s house and we started chatting, trying to stay cool while the war around us was heating up. Nothing breaks the ice between people more than the shared experience of shelling.

At around 3 p.m. the Alliance forces started hitting Taliban positions on the hill ahead.

Mortars fired in the trench behind us as Katyusha rockets whizzed overhead on their way to Taliban trenches.

The Taliban responded without much enthusiasm, lobbing shells way off the mark, the closest landing about 200 metres from our trenches. Paul, Volker and I ducked just in case.

But it was close enough for Commander Muhammad Bashir, who immediately ordered three tanks to open fire at the Taliban positions.

The tanks fired with a deafening thud, releasing an enormous flash and disappearing in a cloud of smoke and dust. Four armoured carriers started moving up the hill, their tracks screeching on the sand and rock.

Satisfied by the performance of his troops, Bashir pulled out his prayer mat and started his prayers.

Looking at Bashir bending and kneeling on the mat, Volker complained he was suffering from back pain. I offered him some Motrin that I always carry with me in a first-aid kit.

At around 5 p.m. voices on the radio became more excited. “God bless you, Mazar,” Bashir yelled into the radio to one of his platoon commanders who managed to fire a rocket-propelled grenade into the narrow slit of a Taliban bunker, causing an enormous explosion.

Bashir sent the Russian-made vehicles to finish the job. “There are foreigners fighting on the Taliban side. They will never surrender and they fight like mad dogs,” Bashir explained.

By 5:30 p.m., as it was getting dark, Taliban shelling ceased completely. Alliance officers and Western reporters left the trenches to get a better view of what was happening.

“We have captured all five Taliban bunkers, the area is clear,” a voice on the radio said. “We’ve driven them one kilometre from their positions.”

Bashir ordered one of the vehicles to come back. “I’m going there to see what’s going on,” Bashir said.

Volker, who was on good terms with Bashir, asked whether he could ride with him. Other reporters, including me, requested the same favour.

“It might be very dangerous,” Bashir said. “There are mines near the Taliban trenches and the Taliban might launch a counter-offensive.” But the temptation of seeing the almost legendary Taliban trenches and bunkers dug in the hill was too strong.

In complete darkness we climbed on top of the carrier. There were about 12 or 15 people sitting there already. Volker was one of the first ones to climb on. Paul and I found a place next to him. I was sitting on the front right side of the turret, facing forward, holding on to the anti-tank rocket launcher. Paul and Volker were on my right.

Just before we were about to go I saw Pierre Billaud, a 31-year-old reporter with Radio Luxembourg, board the carrier in the back.

I never saw Johanne get on the vehicle. I had seen her a couple of hours earlier. She was descending the hill as I was climbing it. We waved to each other and continued on.

Once everybody was on, Bashir, who was sitting in the commander’s seat behind the driver, gave the order to move ahead.

The powerful engine revved, sending hundreds of sparks out of the exhaust pipe, and the vehicle jerked forward, gathering speed.

The driver followed exactly in the tracks of other vehicles, where small craters indicated anti-personnel mines that were set off. I prayed the Taliban did not lay any anti-tank mines. We passed a first line of trenches that looked exactly like the Alliance trenches we had just left.

Approaching the second line, we passed an Alliance platoon marching toward Taliban positions. The second line of trenches was bombed much heavier than the first and a huge crater blocked our way. There was no sign of bodies or abandoned equipment.

The fighting had subsided considerably and only occasional red tracer bullets could be seen flying gracefully from one position to another.

The armoured personnel carrier negotiated its way around the crater, its tracks screeching busily in the softened soil.

It was gathering speed after passing the crater when, suddenly, shots rang out barely 30 metres to the right of us. At least one machine gun and five AK-47s were firing at us, their muzzle flashes illuminating the night.

As soon as the first shots were fired people started jumping from the armoured carrier.

Volker, who was sitting on the edge, appeared to be one of the first ones to jump. But he had been shot in the head and went into a death roll off the armoured carrier.

“Mines and unfamiliar territory, don’t jump!” flashed in my mind.

Volker, in his green Uzbek coat rolling on the ground like a stuntman, was one of the last things I saw before the driver made a sharp left turn and started descending a steep hill. Those who had nothing to hold on to fell down.

I was thrown in the air as we jolted violently and landed a metre away, flat on my back atop the armoured carrier, holding on to the cannon.

Bullets started ricocheting off the armour; then I heard the familiar sound of the rocket- propelled grenade and caught sight of an orange ball of fire moving fast in our direction.

In the second it took the rocket to hit us I remember thinking: “If it’s an anti-tank RPG, we’re fried.” The back doors of Russian armoured personnel carriers are hollow and serve as gas tanks, even a large calibre machine gun can turn the vehicle into a moving torch if it hits the doors.

The carrier shook as the grenade hit us and I felt the explosion roll over me. Fortunately, it was an anti-personnel grenade and it didn’t pierce the armour.

A few seconds later, which felt like hours, we got out of the view of the Taliban gunners. We reached a hollow and the driver turned off the lights and stopped.

“Levon, you speak French don’t you?” I heard Paul’s voice. He pointed toward somebody lying face down and holding on to the straps on the side of the turret. I had met Veronique Rebeyrotte, a Radio France reporter, at Dr. Abdullah’s press conference.

“We are missing two French reporters, Pierre and Johanne,” Veronique said. “I think their translator is missing too.”

“Se journalista kharija wa yak tarjman [Three foreign reporters and an interpreter],” we yelled at Bashir, pointing him overboard.

Bashir immediately got on the radio repeating our message to somebody on the other end. Then Bashir, the driver and two other soldiers who had managed to hang on to the armour started arguing. After they reached a consensus the driver backed up to another hill. But almost immediately we were under fire from another group of Taliban fighters. Red tracer bullets flew overhead, barely clearing the turret.

After several sharp turns in different directions, which left me disoriented, we found another hollow to hide in. We heard voices and one by one people started showing up, appearing like shadows from the darkness.

After waiting several minutes, Bashir and the others decided to change position again.

We were under fire again but more people found us in the new position. Now only Volker, his interpreter, Pierre, Johanne and their interpreter were missing.

We waited some more but there was no sign of the missing. Finally Bashir sent scouts to reconnoiter the way out. Half an hour later the scouts returned and guided us down a rocky ravine and back to the foot of Chaghatay.

Bashir sent a search party to look for the missing people and invited us to his tent. Veronique started making phone calls to editors.

As we sat in the tent cross-legged, eating rice with our hands, there was no sense of the tragedy. It seemed that Volker and the others would walk in any minute.

Then at around 9 p.m. we heard the word “kharija” over the radio and ran out.

As we were getting closer, Massoud, my translator said: “She was killed.” Johanne lay there as soldiers in tank helmets stood on the armour and shook their heads in disbelief. They said she was found in the Taliban trenches. The search team had to attack the trenches to retrieve her body. They said there might have been another body but they could not get to it.

“Can you come up with us to the ministry of defence?” the vehicle commander asked me. “We need somebody to hold her so she doesn’t fall over.”

Volker and Pierre were found dead early in the morning. They, and Johanne, are the first foreign journalists to die in Afghanistan. Their interpreters are still missing.

journalists killed on the frontline near the village of Chaghatay in Khoja Ghar district in Takhar province, Northern Afghanistan, November 12, 2001.